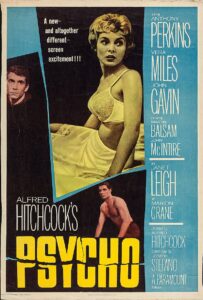

Horror films depend on sound perhaps more than any other genre. Not only can a great score like Bernard Herrmann’s work on Psycho terrify us by tapping into our primal instincts and evoking our danger responses with shrill and staccato strings, but conversely, the deliberate absence of sound can be just as terrifying:; leaving the audience in a constant state of suspense. This approach can be heard, or rather not, in John Krasinski’s A Quiet Place wherein the silence provides the viewer with far more terror and immersion than any non-diegetic sound could have.

Horror films depend on sound perhaps more than any other genre. Not only can a great score like Bernard Herrmann’s work on Psycho terrify us by tapping into our primal instincts and evoking our danger responses with shrill and staccato strings, but conversely, the deliberate absence of sound can be just as terrifying:; leaving the audience in a constant state of suspense. This approach can be heard, or rather not, in John Krasinski’s A Quiet Place wherein the silence provides the viewer with far more terror and immersion than any non-diegetic sound could have.

However, arguably the single most iconic horror soundtrack comes from longtime Spielberg collaborator and film score hall of famer, John Williams. The low rumblings of double bass and cellos combined with frantic trombones that soundtrack the nautical terror of Jaws have essentially become sonically synonymous with the very notion of suspense in the cultural zeitgeist, which is an enormous testament not only to the immeasurable talent of Williams but also the ability that music has to transform a horror flick from a frightful flop to an instant classic. The iconic theme does what all great themes should, it builds a strong association between the music and the appearance of the subject (in this case, the shark). However what Jaws does so excellently is to use this association to subvert viewer expectations with frightening consequences. Throughout the whole picture, the shark has appeared with due musical warning, so when it erupts onto the screen in the last act without a single note in earshot, it elevates the jumpscare to new heights.

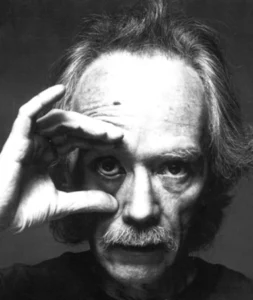

But It just isn’t possible to speak about music and horror without addressing the undisputed king of combining those worlds: John Carpenter. Born in postwar America and the son of a music professor, Carpenter spent his early life watching the low budget horror films of the 1950s. It wouldn’t be long before he was able to coalesce these two important early influences and in 1970 he would act as co-writer, film editor, and music composer for a short student film that would go on to win an Academy Award. His first directorial role came in 1974 with Dark Star and since then he has weaved an incredibly acclaimed filmography boasting iconic titles such as Halloween, They Live and The Fog, all of which he also scored.

But It just isn’t possible to speak about music and horror without addressing the undisputed king of combining those worlds: John Carpenter. Born in postwar America and the son of a music professor, Carpenter spent his early life watching the low budget horror films of the 1950s. It wouldn’t be long before he was able to coalesce these two important early influences and in 1970 he would act as co-writer, film editor, and music composer for a short student film that would go on to win an Academy Award. His first directorial role came in 1974 with Dark Star and since then he has weaved an incredibly acclaimed filmography boasting iconic titles such as Halloween, They Live and The Fog, all of which he also scored.

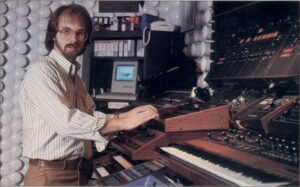

Although, it may be surprising to hear that Carpenter’s most iconic and influential score (Halloween, 1978) came not from artistic decision, but financial constraint. The 1970s were the beginning of an experimental era in the genre, but also an era of limited budgets and resources. Halloween was given a budget of only $325,000, with Carpenter receiving $10,000. This left little room for the luxuries of a composer or orchestral ensemble, so Carpenter took it into his own hands and produced the entire score. He used the emerging technology of synthesisers and electronic music to create a refreshing and unique take on what a horror film should sound like.

Electronic music was new, and unfamiliar. It gave the world an often idealistic glimpse into the future and, what game-changers like Carpenter were able to do is take that unfamiliarity and extract its more sinister and pessimistic undertones, exploiting the common human fear of the unknown.

Carpenter’s legendary soundtrack for Halloween along with Claudio Simonetti’s synth focused, groundbreaking soundtrack for Suspiria a year prior successfully paved the way for a new sounding generation of horror films (many of which were still composed by the prolific two). Even Ennio Marricone, who is widely regarded as one of greatest classical composers of all time, perhaps known best for his contributions to the western genre, when enlisted to compose a score for John Carpenter’s The Thing, opted for a synthesiser heavy approach in the aims of ‘making it sound like a John Carpenter movie’. Indicating that between Halloween in 1978 and The Thing’s theatrical release only 4 years later, Carpenter had already successfully created a new signature sound in the cinematic world of horror.

The landscape of music for horror is still constantly evolving and auteurs continue to push boundaries, finding new ways to innovate in a genre seemingly so devoid of untrodden paths. From Nosferatu to It Follows, the tapestry of sound is only getting richer. A good horror film is made great by the sounds with which it frightens us, keeps us awake at night, and has us trepidatiously tip-toeing into the shallows of the sea, awaiting that dreaded double bass and the unspeakable monster that it beckons.